VERUM PULCHRUM BONUM, 2020-22 |

The 1960s saw early Conceptual artists such as Yoko Ono, On Kawara, and John Baldessari employ language as the primary medium in their works. This seemed to be the natural outcome of an age obsessed with the question: “What is art?” For indeed a question begs an answer and an answer is easily expressed with words. By using words and almost only words (for even words require a medium), these artists argued that art is essentially ideas qua ideas, and that any other aim such as usefulness, ornamentation, edification, and transcendence had become obsolete, or at best, excessive. Whether or not this was right, the supposition prevailed, establishing the text-based art genre and the spirit of making art to “make a statement.” Sixty years later, witticisms, politics, false truisms, and cynical obscenities have become cliché in the art world. Some such works fetch multi-million dollar biddings. Many more populate our public museums. All of this left the artist wondering what place the Christian worldview has in this dialogue. These three paintings, echoing the earliest works of the text-art genre, introduce Christian ideas to the conversation.

The Messiah taught His Apostles, “the truth will set you free” (Jn 8:32), and by extension, all of us. (Indeed, it was the Word and words like these that drew the artist from a life outside of the Faith into one inside of it.) The verse is worth our unending contemplation and faithfulness. Careful readers will note that the promise is conditional. The full statement reads: “So Jesus said to the Jews who had believed him, ‘If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.'” (8:31-32, emphasis mine). The Evangelist elaborates this idea when he records the Lord proclaiming Himself as “the way, and the truth, and the life” (14:6, emphasis mine). It is thus in a very direct sense that the truth will set us free, for the truth is a person, that person is Christ, and Christ is our Savior.

Even to non-Christians—i.e. through a stunted understanding of truth as something apart from Christ—we know from the Apostle Paul that all truth ultimately points to Him. God has given mankind a rational faculty to make sense of the world around him; “His eternal power and divine nature [can be] clearly perceived… in the things that have been made” (Rom 1:20). Therefore, a wise and diligent pursuit of purely empirical truth will lead eventually to an understanding of the pure spiritual truth, that truth which is embodied in the body of Christ. By this may men be set free.

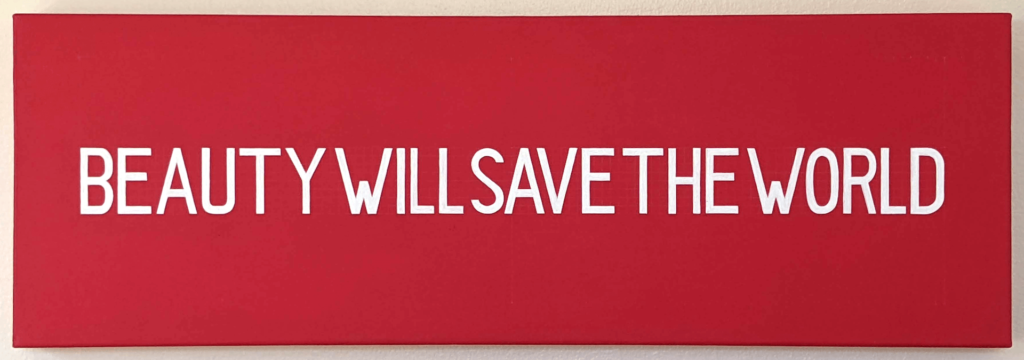

“Beauty will save the world” is paraphrased from the fifth chapter of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot.” That beauty actually can and will save the world is something believed by the protagonist, Prince Myshkin, a “zealous Christian,” and certainly by the author himself, also a zealous Christian. And who would disagree? It is only those who do not understand what beauty truly is. For the Psalmist sings: “Out of Zion, the perfection of beauty, God shines forth” (Ps 50:2), and from this we realize what is already plain before our eyes: that beauty is an essential characteristic of God. Indeed, we can know beauty by its godliness, and godliness by its beauty, and as Christians we are called to cultivate both. Beauty will save the world because He Who is the very “perfection of beauty” has already claimed His victory over it.

There is a notable irony in this piece. Its objective form—rather plain and unimaginative—is not beautiful, yet the message, because it is good and true, is. The artist, however, rejects a gnostic theology which separates the material from the spiritual, i.e. material beauty from spiritual beauty. Rather, the artist recognizes that he is in (but not of) a culture in which beauty is falsely believed to be “in the eye of the beholder,” a culture in which reductivism has diminished both our art and our relationship to God. In a sense, the artist has tried to imitate Christ’s incarnational condescension by delivering his message in a form and language that is familiar to his audience. As the Man “who knew no sin” became “sin” “for our sake” (2 Cor 5:21), so this work presents a beautiful truth—that “beauty will save the world”—in a style devoid of style.

The question of what art is arises from a concern about what art is for. Many since the 19th century have concluded that art, rather than to serve a higher purpose, should be made for its own sake. This goal, however, is not only not possible, but it makes an idol out of art, as if art has a sake and that artists should strive to serve it. Instead we might consider the Apostle Paul’s instruction: “Let all things be done for edification” (1 Cor 14:26). Indeed, the pursuit of goodness is the right and proper end for all human actions, the creation of art notwithstanding. As “Every good thing… is from above” (Jas 1:17), so should artists strive to reflect this goodness that comes down from God in their work. This piece presents the word “GOODNESS” alone, carefully painted on a canvas, to make this point—for truly, any other aim “is vanity” (Ecc 1).

It is obvious that the word “GOODNESS” is not in and of itself goodness; it is merely, as is known in semiotics, a “signifier” to a “signified.” This disconnect between form and content is meant to highlight an inherent problem in the text-based art genre. Ironically, Conceptualists have exploited this discrepancy from the beginning. BONUM cites two examples: John Baldessari’s “Pure Beauty” (1966-68), which is a painting of the words “PURE BEAUTY”, and a circa 1965 painting by On Kawara of the word “ART”. The wit and cynicism of these two works are overt, and this piece, with surprising sincerity, imitates them as if to undermine them: to turn what was turned upside down upside down again. (Likewise, VERUM and PULCHRUM copy the form of another painting by Kawara of the phrase “GO HOME AND CRY ON YOUR PILLOW”).